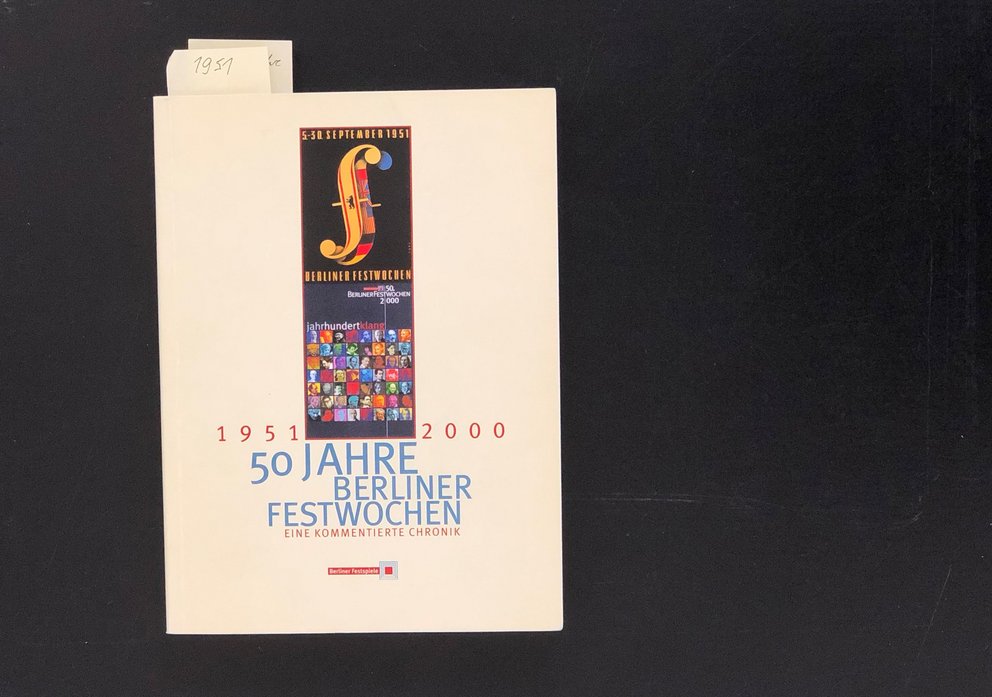

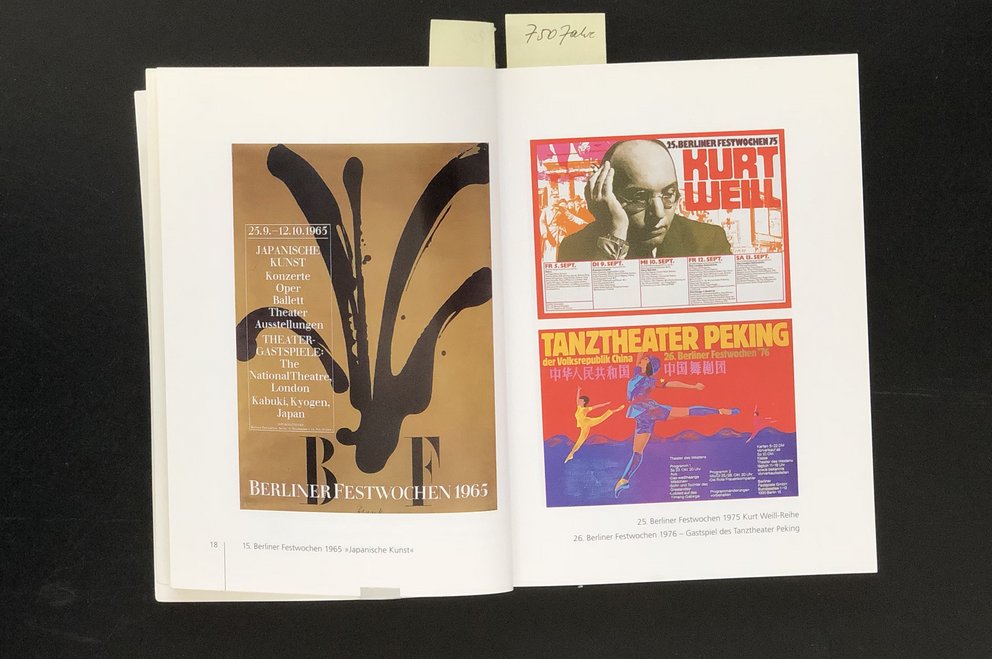

Of course, Tanz im August didn’t just appear out of nowhere. Its history is a part of the history of Berlin, and begins in the post-war period – in 1951, to be precise, when the international art world was first invited to a divided Berlin for the Berliner Festwochen and the International Film Festival.

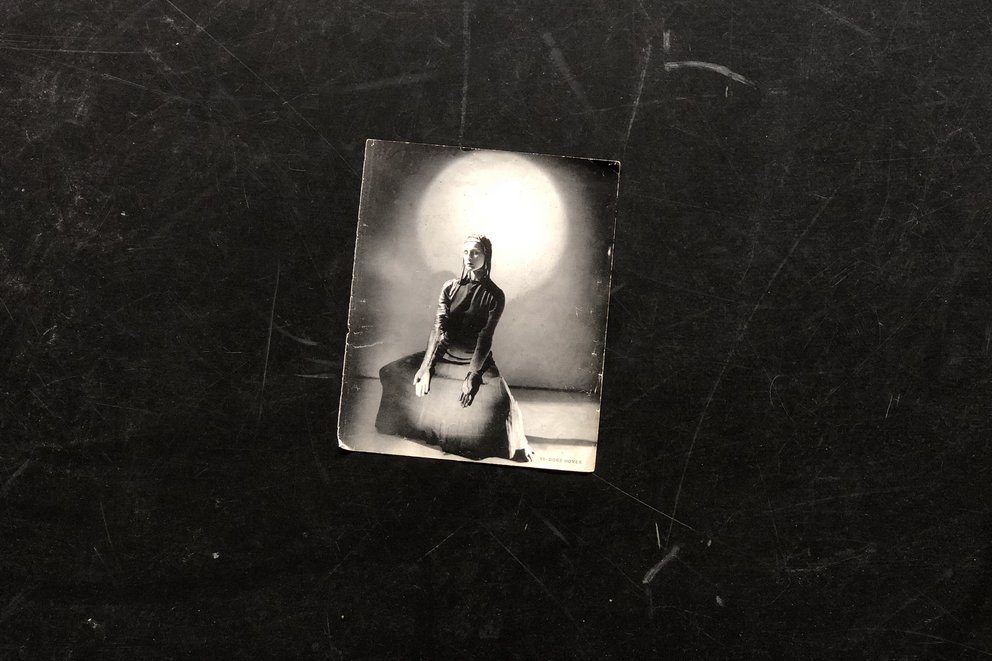

While in East Berlin the so-called ‘formalism vs realism debate’ had made its way into the uppermost levels of the political hierarchy, with the central committee of the SED in March 1951 declaring war on formalism in the visual arts, music, set design and ballet, and denouncing “so-called” Ausdruckstanz (Expressionist dance) as incomprehensible and unintelligible, in West Berlin there was an attempt to show what had been happening elsewhere, to show how art had developed during the time that Germans had only believed in the importance and validity of Germanness in art. On 5 September 1951, Berlin mayor Ernst Reuter wrote on the occasion of the opening of the Festwochen (and the inauguration of the Schiller-Theater):

“It seems a risky venture, here in Berlin, this besieged and divided city still suffering the after-effects of the war and the post-war period, to put on something like the Berliner Festwochen. Is it fitting, one might ask, to put on festivals when the strains and stresses of our time are weighing so heavily upon communities and individuals alike? The answer is yes – festivals are also necessary, and are an integral part of Berlin life…that is the reason for the Berliner Festwochen; to show the East and the West that hardship and suffering, debris and distress do not cause the eternal wellspring of the creative spirit to run dry, that theatre, music, and visual arts make Berliners’ lives beautiful and worth living, and will continue to do so…”